How Christian Nationalism and High-Control Catholicism Shape Extremism

A Whiplash Podcast Recap Essay

“Don’t you know the Devil wears a suit and tie?”

-lyric from country-folk song “The Devil Wears a Suit and Tie” by Colter Wall

Authoritarianism is not hiding in the shadows. It’s organizing in front of us: with slick graphic design and polished media production, funded by big money with deep pockets, and networked internationally. It also thrives on politeness politics, hoping you won’t call it out because every unchallenged moment of deference buys it more time to grow. Authoritarianism values the comfort of the oppressor over the experiences and existence of the oppressed, as seen in the recent firing and censorship of media personalities and professors who spoke out about Charlie Kirk’s problematic legacy.

On this week’s episode of our podcast, we spoke with Dr. Joan Braune, a philosopher who has spent almost a decade working to help expose these movements and organizing frameworks of resistance against them. Joan is not only a professor at Gonzaga University and an editor with the Journal of Hate Studies; she’s also been on the ground with communities, helping them understand and dismantle far-right recruitment tactics. Her forthcoming co-edited work on Christian Nationalism promises to be just as urgent. Read more on her blog or on Academia.edu.

In our conversation, Joan revealed how fascism operates not as a fringe problem but as a coordinated social movement—equipped with leaders, funding streams, media ecosystems, and international connections. She warned that quick fixes like elections or policing alone won’t stop it; instead, we need organized, collective resistance. She also dissected the myth-making at the heart of fascist rhetoric, from Catholic Steve Bannon’s recycled, ancient Roman “cycles of history” to the pseudo-intellectual narratives that high-control religious movements often weaponize under the guise of tradition.

This essay is a recap of that podcast discussion. In the six sections that follow, we’ll unpack Joan’s insights in more detail—from the mechanics of fascist organizing, to the myths that give it fuel, to the connections with Christian nationalism and high-control Catholicism that intersect directly with our own work (and the book we’re currently working on!)

Section 1: Joan Encounters Fascism

Joan didn’t set out to study fascism. Her training was in philosophy, and when she moved from Wisconsin to Washington State, she expected a landscape of progressive activism and countercultural communities. Instead, she found herself in a region long targeted by white supremacists as a safe haven. Eastern Washington, along with neighboring Idaho, Montana, and Oregon, had been shaped by decades of white nationalist migration strategies, including the so-called “Northwest Territorial Imperative”—a push to create a separatist stronghold in what was already one of the whitest areas of the country.

Another good example is Moscow, Idaho, which serves as home base for the self-described Christian nationalist pastor Doug Wilson. Wilson is the co-founder of the Communion of Reformed Evangelical Churches and pastor at Christ Church in Moscow. Wilson has actively called to make Moscow, Idaho a “Christian town.” Like St. Marys, Kansas, a separatist community established by and for traditionalist Catholics (we covered St. Marys here), Wilson hopes to transform Moscow through an explicitly Christian governance structure, and in MAGA Christianity, his Christian crusade for control has found an eager audience among Trump supporters and cabinet members.

Wilson’s name may sound familiar because this past August 2025, Wilson shared in a video interview with CNN that he believes women should not have the right to vote. The video exploded when Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, a member of Wilson’s church, reposted the video.

Even more recently, Evangelicals pushed for a rapture scheduled for Tuesday, September 23rd and Wednesday, September 24th, eagerly awaiting to be vaulted into the sky and #RaptureTok exploded on Christian TikTok. As criticized online, some evangelicals seemed all too happy to embrace the End Times as opposed to taking accountability. On that note, Olivia Bardo wrote for the National Catholic Reporter, “we can’t schedule a midweek rapture and cash in on an easy escape. We still have work to do.”

Echoing the theme of sitting with the present moment rather than disassociating in an end-times fantasy, Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde, who delivered a challenging homily at the January 2025 interfaith prayer service following Donald Trump’s second presidential inauguration calling for compassion and mercy toward marginalized groups, recently asked on her Substack, “What is life like for you in America now?” with respondents chiming in from across the country in the comments. In contrast to pastor Doug Wilson pushing for separatism, isolation, and rigidly sexist gender roles, Bishop Budde uses her platform and role as a spiritual leader to call out complicity while creating space for people to process and take stock of the present moment.

Back to Joan: while Spokane has its own rich history of resistance and labor organizing, Joan quickly realized she was living on the fault line of an ongoing battle. Her academic research at the time focused on Erich Fromm’s critique of apocalyptic thinking—the idea that society needs to be destroyed and reborn through catastrophe (more on that theme later). When the 2016 election was unfolding, Joan began to see chilling parallels between Erich Fromm’s warnings and the ideology of Steve Bannon, a Catholic who was then one of Trump’s most influential advisers. Recognizing these connections, Joan started speaking publicly about Bannon’s worldview and its fascist roots, drawing attention to how it was shaping American politics.

Through this work, she connected with veteran activists who had spent decades resisting groups like the Aryan Nations, once headquartered in nearby North Idaho. That intersection—between her philosophical research and the lived realities of fascist organizing in her new home—pulled Joan into a dual role as both scholar and activist. For nearly a decade now, she has been studying the far right while also helping communities recognize, understand, and resist its influence.

Section 2: Definitions

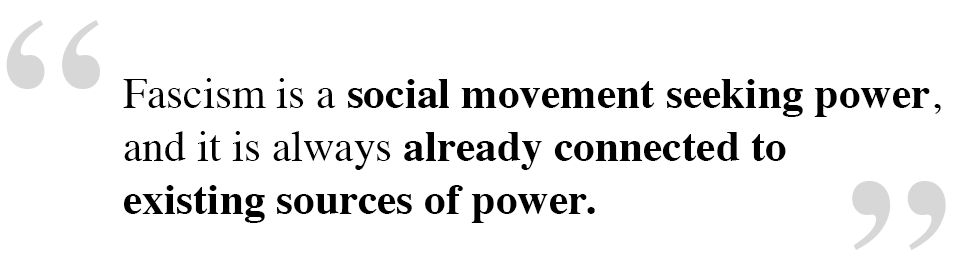

One of Joan’s most important contributions to the conversation is her insistence that fascism cannot be reduced to a handful of extremists who can be policed, jailed, or dismissed as outliers. As she explains, fascism is not just criminal behavior—she defines fascism as a social movement seeking power, and it is always already connected to existing sources of power. This framing helps us see why superficial solutions like policing or elections are not enough.

The “blend in” strategies that became more visible after the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville in 2017 show how fascists are not merely thugs with swastika tattoos but individuals and organizations that can deliberately mainstream their appearance and messaging to gain legitimacy and influence. It also explains why Manoverse influencers and MAGA leaders have attempted to portray themselves as a conservative elite, despite appealing to and relying on the voters and labor of working class Americans.

This is where Joan takes issue with what Homeland Security calls “squishy power”—state-run prevention programs that imagine social workers can gently redirect people out of hate groups. While she acknowledges that prevention work has value, she cautions against the fantasy that state power can be wielded neutrally in this fight. Fascism is not waiting to be arrested; it is building power with leaders, media platforms, funding pipelines, politicians, and international allies. To misdiagnose it as a matter of “bad individuals” or a “couple of rotten apples” is to miss the full picture, where the very power systems that seek to reign in fascism actually often fuel it.

Instead, Joan insists that only organized resistance movements—anti-fascist social movements rooted in solidarity and collective power—can effectively counter fascism’s reach. When harassment in a local town, a viral podcast, or an isolated act of violence emerges, it is never just about that incident. Each connects back to a broader network, one that cannot be dismantled by piecemeal interventions. The only answer, Joan argues, is to build something stronger in return.

Section 3: View of Time and History

The Myth of “Insider Knowledge”

Joan points out that one of the most revealing aspects of fascist ideology is the way it manipulates ideas of history. Instead of the Christian vision of time moving toward a kingdom of God, a messianic age, or a beloved community marked by justice and peace, fascist thinkers turn back to ancient Rome and a cyclical view of history. Building on essays we’ve done about masculinity, the fascination with ancient Roman culture is clearly tied to Manoverse influencers, who cosplay as crusaders and Roman officials. Pete Hegseth, Secretary of the newly coined Department of War, has the Jerusalem cross, (also known as the Crusader cross), tattooed on his chest and “Deus Vult” (a Crusader battle cry) on his bicep. As Joan notes, those who ascribe to authoritarianism are not quiet or subtle about their alliance to and indeed, active support for, this type of power.

Within the cyclical view, history is framed as an endless cycle of rise and decline: strong men restore order, weak men lose it, and the pattern repeats. This is the worldview Steve Bannon and others on the far right have championed, a pseudo-intellectual scheme that makes hierarchy and violence appear natural, even inevitable. When people repeat memes like “strong men make good times, weak men make bad times,” a reference to G. Michael Hopf’s book Those Who Remain, they are not drawing on Christianity at all—they are parroting ancient Roman fatalism, repackaged for modern use.

This contrast is crucial. Christianity’s vision of history is linear, moving toward a final horizon of hope and justice—the kingdom of God or a beloved community. Fascism’s cyclical determinism is an endless cycle of fatalistic suffering. Christian nationalism often collapses the two, disguising Roman myth as “tradition” and presenting it as authentic faith while denying the real history. This mirrors the tactics of High Control Catholicism, where followers are convinced that only a select few understand the “real” meaning of scripture, ritual, or doctrine. In both cases, the promise of insider knowledge functions as a tool of authority, shaping behavior, loyalty, and even belief.

The result is a dangerous, molotov cocktail: pseudo-Christian leaders borrowing ancient Roman myths, tech billionaires weaving grand narratives about crusades and civilization, and authoritarian Catholic figures weaponizing the language of tradition to control their flocks. Manoverse influencers and techbros, for example, idolize ancient Rome while conveniently denying that same-sex relationships were common and visible—an erasure that goes hand-in-hand with their ostracization of queer people today.

As Joan warns, this isn’t simply misguided theology—it’s a carefully engineered ideology of power. Once these beliefs are cast as “ancient wisdom” provided only to the true believers, it becomes almost impossible to challenge with reasoned debate or better theology. By masquerading as hidden knowledge, fascism and high-control religious movements alike make themselves feel inevitable, essential, even sacred.

Section 4: Gender, Hierarchy, and Radicalization

Joan highlights that gender roles are deeply intertwined with the radicalization process and the appeal of Christian nationalism. Far-right movements offer men—and others from dominant groups—a sense of power and purpose, framing personal grievances, alienation, or economic precarity as the result of societal enemies. Women also play active roles, but often under the guise of powerlessness: their influence is exercised through organizing, recruiting, and shaping narratives, while their physical appearance and sexuality are scrutinized and instrumentalized. This dynamic mirrors patterns seen in high-control religious movements, where authority is maintained by controlling how followers present themselves and understand their place within a hierarchy (and almost always includes very rigid gender roles).

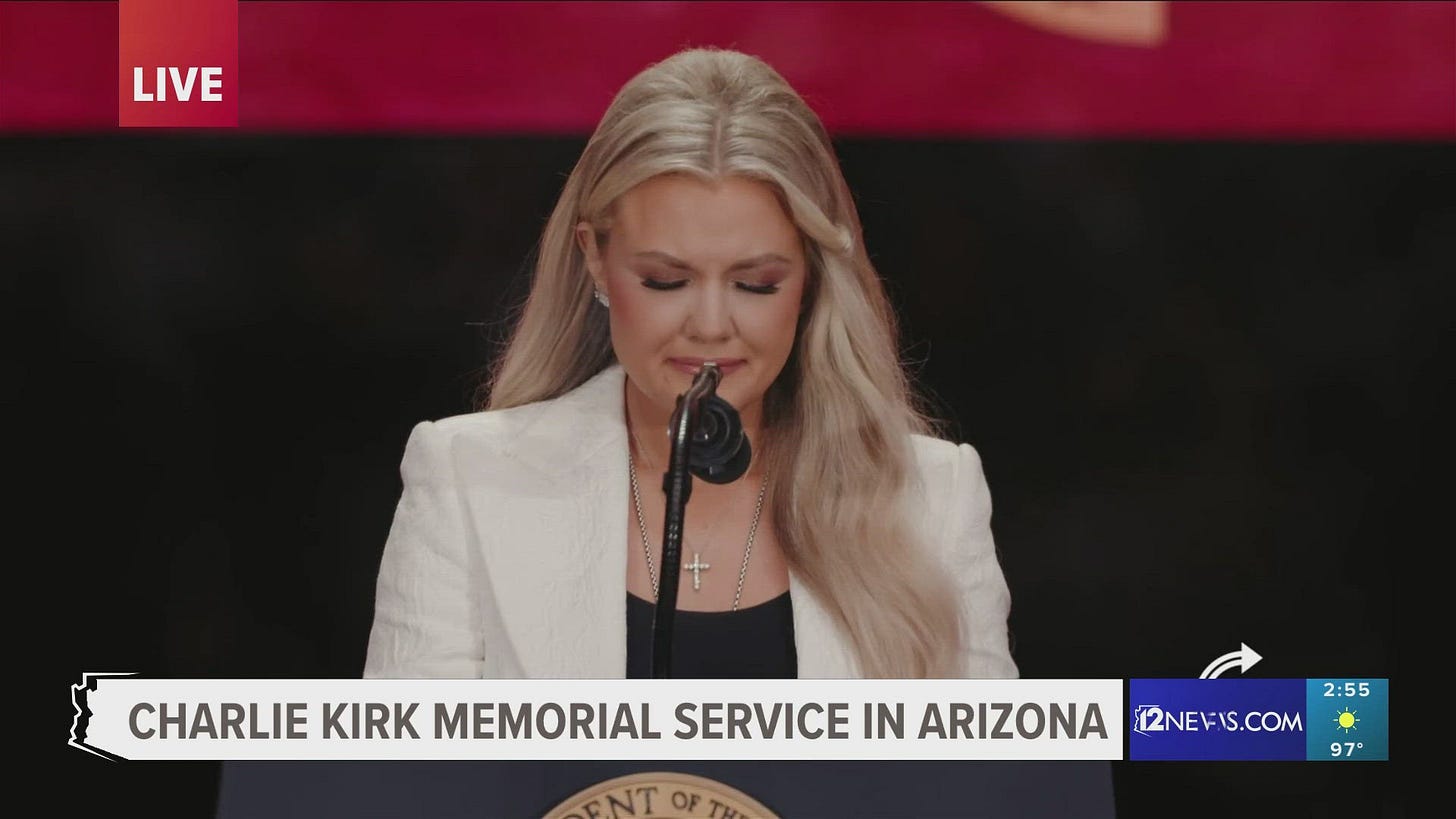

A great timely example of these themes can be seen in Erika Kirk speaking directly to women at the memorial for her husband. In this moment, Erika became a champion for tradwives looking for leadership–a MAGA Phyllis Schlafly: a powerful white woman who profited off the rights feminism afforded her while rallying against it. Ultimately, Erika is using her political and financial capital to argue against her very existence. A day after her speech, far right pastor Taylor Marshall posted a video claiming that “Erika Kirk just ended the Feminist Movement,” arguing that “true Christian femininity was on display.”

Related: “Charlie Kirk and the Illusion of Debate”

Like Schlafly, Erika Kirk mobilizes a growing minority of conservative (largely religious) women that are increasingly dissatisfied with fifth wave feminism and, like young men, are being pulled into conservative far-right Christian movements. Tradwives are the dangerous realization of this movement, and the very people that Erika Kirk has positioned herself to lead. Just as Erika Kirk implored the young men listening on Sunday to “accept Charlie’s challenge and embrace true manhood,” reinforcing Charlie’s martyrdom for “family values,” Erika situated herself as his compliment—the ultimate White woman victim.

Race and class further structure far-right movements. From suit-and-tie intellectuals to street-level enforcers, far-right groups maintain internal hierarchies that dictate who wields power and how. White supremacy underpins the entire system, creating a framework in which some lives and bodies are seen as more valuable than others. Joan emphasizes that this hierarchy is not always explicit—it is normalized in everyday culture and reinforced through institutions like homeschooling curriculum, churches, and local schools, shaping perceptions of history, authority, and legitimacy from a young age.

The result is a complex ecosystem in which ideology, identity, and social structure feed one another. Radicalization is not simply about individuals making bad choices (rotten apple); it is facilitated by systems that promise status, belonging, and clarity in a confusing world. The “live option” of fascism—its presence as a conceivable path in American society—reveals how deeply supremacist assumptions are embedded in cultural, educational, and religious norms. Understanding these dynamics is crucial if resistance is to be more than reactive, requiring a reckoning with the underlying hierarchies that make extremist movements appear feasible or even natural.

The American school system has, historically, taught about the evils of the Nazi German regime and often vilifies those who stayed silent, passive in the face of escalating violence. In learning these histories, we often think to ourselves that we would be the ones to speak out. We wonder, sometimes even leaning into White savior fantasizing, about who we would be during an authoritarian regime. Well, as Braune highlighted in this past Monday’s podcast, we’re finding out right now. ICE is disappearing immigrants and people of color and putting people in decrepit detention camps, and far-right political leaders are denying the personhood and dignity of trans and queer people. We will explore ways to organize and resist in Section 6.

Section 5: Catholic Involvement

Joan emphasizes that Catholics, like other religious groups, have not been immune to the strategies of fascist entryism. Within the Church, the same dynamics of “insider knowledge” that appear in high-control Catholicism—claims that only a select few understand the “real” faith—can be co-opted to normalize far-right ideologies. This has played out both culturally and tactically, as some individuals enter parishes and Catholic institutions under the guise of being “traditional” or “conservative,” only to organize for fascist causes from within.

Related: “Exploring Catholic Nationalism”

Figures like Nick Fuentes illustrate this phenomenon: though he frequently presents himself as a practicing Catholic, those close to him report he rarely attends Mass. This is not to suggest we are policing the sincerity of anyone’s belief, but rather to show how Catholic identity can function as a cultural marker of legitimacy and insider culture, wielded strategically by individuals whose broader ideology is radically at odds with Catholic teaching.

In fact, a 2023 study by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) identified growing interest in Catholic Integralism and traditionalism among far-right America First and Groyper movements (both groups associated with Nick Fuentes), mobilized on social platforms like Discord. ISD researchers found consistent violent rhetoric. “Users and admins,” they write, “at times implied that there was a need for violence to fight ‘degeneracy and the modern society.’ In one instance, a user similarly shared a quote by 2015 Charleston shooter Dylann Roof that asks readers to start fighting for the ‘white race’ rather than for alleged Jewish interests. Lastly, there were some memes shared that centered around the mythical figure of St. James the Moor Slayer and celebrated the killing of Muslims.” The latter is a connection to Crusader culture among far-right circles.

Once again, Charlie Kirk’s memorial sparked several good examples of this. Far-right commentator Jack Posobeic (shown in the image at the top of this essay) walked out on stage brandishing a rosary and compared Charlie to Moses. Militaristic language was thick throughout the speeches, with Posobiec referring to Charlie “his commander.” As a reminder, Charlie Kirk was not raised Catholic, nor was he baptized into the Catholic Church, but Catholic leaders are claiming him as an “almost Catholic” to legitimize their position to far-right power. Cardinal Timothy Dolan praised Charlie Kirk as a “modern-day Saint Paul,” with Bishop Barron calling him “a kind of apostle of civil discourse.” Both were criticized by Catholic media publications, and Dolan was even called to task by the Sisters of Charity in New York.

The interplay of politics and Catholicism is also evident in the broader alt-right strategy. After the violent split in the alt-right following the Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally in 2017, some factions pursued overt, genocidal action, while others embraced entryism—embedding themselves into mainstream institutions, including churches, charities, and political organizations, to recruit and influence from within.

This approach parallels historical patterns within High Control Catholicism, where resistance to democratic ideas and embrace of hierarchical authority has long existed, dating back to anti-revolutionary movements in response to the French Revolution. In the contemporary moment, that tension finds new expression through assimilationist strategies as seen in figures like JD Vance and others converting to Catholicism or adopting its symbolism as part of a broader political narrative tied to Christian Nationalism.

In our podcast conversation, Joan also highlights the dissonance between these fascist-aligned approaches and core Catholic philosophy. Influenced by thinkers like Saint Thomas Aquinas, Catholic thought emphasizes that all—including rulers—are subject to law. Yet modern fascist ideologies often champion a ruler above the law, a Catholic king: a stark contradiction to these theological foundations. This tension underscores both the strategic appeal of Catholic identity to far-right organizers and the dangers of treating religion as a cultural badge.

Normalizing fascism as a politically viable “option” within American Catholic spaces is a relatively novel development, and understanding the ways in which Catholics—culturally, symbolically, and organizationally—are mobilized is essential for resisting its influence.

Section 6: Organizing Against Far-Right Movements: Where to Focus Energy

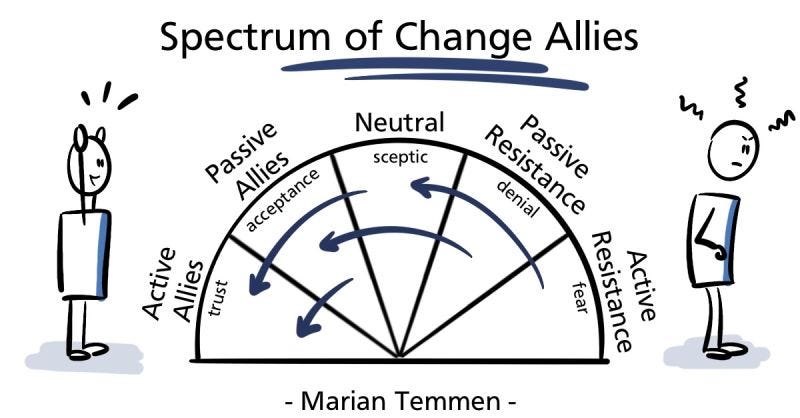

When it comes to resisting far-right and fascist movements, Joan emphasizes the importance of directing energy strategically–and locally! She draws on the “spectrum of allies” framework: at one end are committed activists already taking action, then passive supporters, neutrals, and finally active opponents of your cause. The key is to focus on those in the middle and on the sidelines—neutral individuals, passive supporters, and potential allies—rather than expending effort trying to convert entrenched fascists or Christian nationalists.

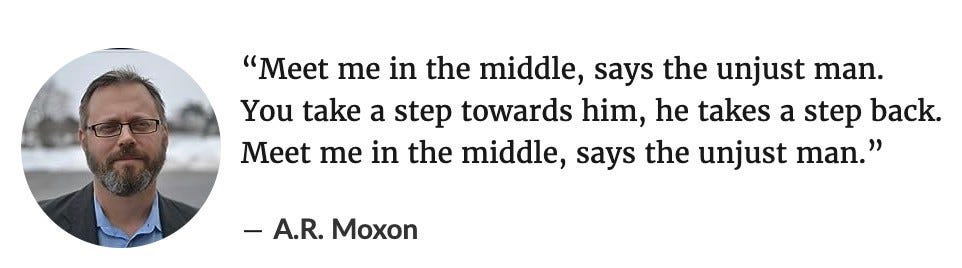

Engaging those who are already radicalized is often dangerous and largely unproductive. Instead, energy is best spent raising awareness, mobilizing new supporters, and strengthening networks of people already sympathetic to the cause. This is why Jubilee debates are not effective; by inviting a fascist to the table, by inviting a transphobe to the table, we give them legitimacy and the ability to take up space. Opposition to fascism is not equal: fascists not only want to isolate marginalized groups but to exterminate them.

On our podcast episode, Joan cautions people from only following former insiders of fascist movements. While their lived experience is to study and share the most effective ways to leave the movements, they are not key organizers or scholars who have done this work for years. They also in some ways represent and retain authority within the movement–and platforming them can be retraumatizing to people harmed by their actions inside the movement. Instead, we should turn to experts like Joan and community organizers who are fighting fascism.

Joan stresses the urgency of the moment. Currently, public organizing, protesting, and community engagement are still viable without extreme restrictions. Activists are encouraged to pick a “niche” that aligns with their knowledge and passion—whether it’s LGBTQ+ rights, healthcare, youth engagement, or environmental work—rather than trying to address every threat simultaneously. This focused approach allows for sustainable action without burnout. Additionally, maintaining core values is essential: there can be no compromise on the humanity and rights of marginalized groups.

This is essential because while we want to connect with and mobilize neutral individuals, we also recognize that being neutral perpetuates violence. Not everyone has to be involved in every movement, but not taking a stand on specific issues means that we are part of the problem and hold space for the “neutrality” fascists construct as an ethical ground. Every individual, from trans people to Jews, Muslims, Black and Indigenous communities, must be fully defended; granting permission to dehumanize any group only strengthens fascist strategies.

Participation takes many forms, and public activism is not the only avenue. Showing up to protests, attending meetings, and joining ongoing campaigns are vital, but so too is behind-the-scenes work. Those with social or economic privilege—white, cis, or straight individuals—may be able to take on public-facing roles more safely, and that privilege should be used strategically to protect others and amplify collective impact. Importantly, activism builds on existing efforts. Individuals do not need to reinvent campaigns; joining and supporting established initiatives strengthens movements and prevents wasted energy.

Finally, Joan underscores the stakes: fascist and far-right movements are not seeking compromise—they aim to remake institutions and society entirely in their image. This includes educational, political, and cultural spaces, where they seek to create ideologically consistent propaganda rather than tolerate even minor dissent. There is no middle ground to be ceded. There is no situation where a person can be fascist and still a morally upstanding person. Activists must recognize that every act of organizing, every conversation with a neutral party, and every demonstration matters in countering these ambitions. The time to act is now, with clarity, strategy, and uncompromising commitment to human dignity.

Conclusion

The insights Joan shared remind us that resisting fascism requires both vigilance and intentionality. From its roots in ancient-Roman and pseudo-Christian mythmaking to its modern strategies of entryism, the far-right thrives by exploiting cultural markers, hierarchical structures, and narratives of “insider knowledge”—dynamics strikingly similar to those we’ve studied in high-control Catholicism. As our ongoing book project explores, these patterns are not abstract; they shape how individuals internalize authority, interpret doctrine, and make political choices. Understanding the intersections between religious control, cultural identity, and extremist organizing is crucial for building meaningful resistance.

Equally important is recognizing that organized, sustained action—rather than reactive or symbolic gestures (like holding up signs in protest in Congress)—is the most effective tool against these movements. As Joan emphasizes, directing energy toward those on the sidelines, mobilizing allies, and participating in ongoing campaigns can shift the balance of influence. Every act of engagement, whether public or behind the scenes, contributes to creating communities resilient to the allure of authoritarianism. By grounding activism in both principle and strategy, we can counter the narratives of inevitability that fascist movements rely upon.

Ultimately, our conversation with Joan affirms the stakes and the possibilities: the fight against far-right organizing is not only political but also cultural and spiritual. High-control Catholicism offers a lens for understanding how authority, ritual, and belief can be weaponized—but it also shows us how those same frameworks can be reclaimed for liberation, solidarity, and justice. As we continue our work, both on the podcast and in our forthcoming book, our aim is to make these connections clear, equipping readers and listeners to recognize, resist, and transform the forces that seek to undermine democratic and inclusive communities.

Listen to the podcast discussion that inspired this recap essay here on Substack or watch the following YouTube version below.

📅 Upcoming from Maxwell Kuzma

We’re closing out September with a podcast conversation on Monday covering American Catholic Anti-Blackness (followed by a recap essay), and then as we move into October we will shift into our 4 part LGBTQ Catholic history series.

Thank you as always for your support. If you don’t want to upgrade to a paid subscription, consider a one time tip here.

Just when you think you have a handle on exploring the mighty river of Christian nationalism and fascistic movements coursing through society currently, Max and Emma expose the insidious white water tributaries and rip currents you never knew existed. Thank you, Max and Emma!