How Pope Leo XIV Can Use Good Theology to Heal the Church and the World

The Unlikely Election of an American Pope

I used to think the problem with the Church was that theology wasn’t being explained well enough.

If we just clarified the Catechism, I thought, atheists would change their minds, and queer folks would accept the contradiction in “it’s okay to be gay, but make sure not to act gay.” If I could explain repressive interpretations of doctrine well enough, it would help people understand—make them see the reason I, and others like me, clung to this Church. Why we fought to carve out space to belong, even when everything around us seemed to be trying to erase us.

When I was 15 and just logging onto the internet for the first time, I didn’t look for games or entertainment. I was googling Catholic doctrine. I read Church documents on the Vatican website and dug into Catholic Answers and the New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia. I was desperate to understand the theology that had been shaping my life. I wanted to know how the faith I’d been raised in could possibly make room for the person I was becoming.

What I found instead were Catholics promoting conversion therapy.

It wasn’t just fringe voices. These were mainstream Catholic sites and forums offering supposed “healing” for something as fundamental as my humanity. They framed it with philosophical arguments and spiritual language, saying homosexuality could be “cured” by revisiting your relationship with your parents or by better modeling stereotypical heterosexual roles. It was all wrapped in the language of compassion, but the message was brutal: you are broken in a way that straight, cisgender people are not.

I didn’t know how to process it at the time. I only knew how heavy it felt—that the Church I loved was speaking about me in a way that made my existence seem like a mistake. It felt unfair, and it hurt—a lot.

Later, when I worked in conservative Catholic media (from 2015-2020) after completing a degree at a conservative Catholic liberal arts school, I saw how theology was used by those with an agenda. The goal wasn’t ultimately to teach or illuminate—it was to control the story that was told. We didn’t share real, messy stories of faith. We told the testimonials of nearly-perfect Catholics—neatly packaged narratives that proved the point we wanted to make. People were props for a message tailored to a very narrow way of being.

I remember seeing the footage for a video on religious freedom—epic music swelled under images of priests raising the eucharist cut into a montage with American flags rippling in slow motion. The point wasn’t subtle: Catholicism wasn’t just a religion; it was an identity and a tool. It was a quintessential depiction of the “culture war” and a clear line in the sand for American Catholics: an implication that your faith demands this union.

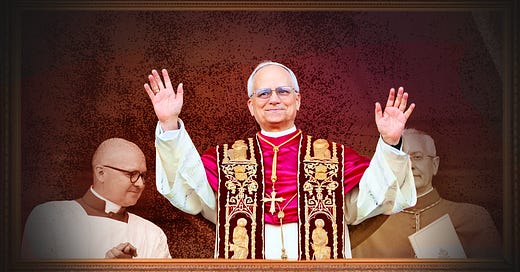

Recently, Trump posted AI-generated image of himself as Pope. The image felt like the natural conclusion of something that started years ago: the unholy alliance of nationalism and Catholicism. And suddenly, many of the same MAGA Catholics who had cheered this fusion were scrambling to say, “He’s just joking.” But he was only joking if they didn’t call him out. This was exactly where they had been headed all along.

In reflecting on this, I’ve understood that theology was never really the heart of the problem. Within nationalist Catholicism, doctrines only really matter if they reinforce power: hence the fixation on issues like abortion, gay marriage, and the human rights of vulnerable communities. If church teaching threatens the power of the state, it is immediately challenged or called illegitimate. Catholic nationalism doesn’t care if it has good theology. It doesn’t care if it’s true. It cares if it wins.

That’s why we can’t just argue better or explain harder. You can’t reason someone out of a worldview that gives them (or people that look like them) power. You can’t debate someone into seeing your humanity when their authority depends on denying it. Orthodoxy and “tradition” aren’t even what truly matter to them. It’s control.

But there’s still hope: as bad as it’s been, theology can still be redeemed by again separating it from the nationalism that has consumed it.

The new papacy is one way we can start down the road towards restoration.

Pope Leo XIV, born and raised in Chicago but now a dual citizen of Peru after spending many formative years of his life as a missionary, challenges the nationalism that has been allowed to fester in America specifically just by his multinational identity. He’s not the man the nationalist Catholics wanted. He’s not a fortress-builder, defender of rigid borders, or bullish on doctrine over people. He’s a global citizen—a pope who embraces the universal Church through policy and even his choice of what language to speak.

MAGA was formed in the evangelical world where a lack of centralized hierarchy made it easier to create a unifying national political identity. In being so quick to try and shore up nationalistic power with Catholicism, they forgot (or ignored) that the Pope is beyond borders.

In an age of instant global communication, his visible existence threatens much of what they’ve built. He is a clear symbol of authority for a global church and a living contradiction to their presentation of Catholic nationalism. His very presence reminds the world: their version of Catholicism isn’t the one practiced in Rome.

The Pope isn’t supposed to be a figurehead for a nation, a political cause, or a movement. He’s supposed to be a servant to the world, representing a faith that transcends national identities and divisions. Pope Leo XIV doesn’t just represent the Church’s universal mission—he has the opportunity to exemplify it, in a way that directly disrupts the nationalist narrative some have tried to impose on the faith.

Leo can offer a reminder that the heart of Catholicism is not about political power or cultural dominance. It’s about global solidarity, compassion, and the universal call to love. Pope Leo XIV represents the possibility that the Church can still be a force for good—not one that divides, but one that unites.

That’s a message that’s dangerous to nationalism. It’s the kind of message that can change things. Bad theology nearly killed me. And it’s killing the Church in America, too. But it’s not too late. We can still reclaim the real heart of this faith. And with Pope Leo XIV in place at the head of a global church, we may begin to see the first steps toward that future.

If you found this piece valuable, consider supporting the work of Max Kuzma—a lifelong Catholic and transgender man who writes and advocates at the intersection of faith, identity, and justice. Your support helps keep his writing free and accessible to those who need it most—like the younger version of him. You can become a paid subscriber to this Substack or leave a one-time tip via credit card, CashApp, Apple Pay, and more at ko-fi.com/maxwellkuzma

Max, I love your writing and depth of analysis. I'll be chewing on this paragraph for a long time..."MAGA was formed in the evangelical world where a lack of centralized hierarchy made it easier to create a unifying national political identity. In being so quick to try and shore up nationalistic power with Catholicism, they forgot (or ignored) that the Pope is beyond borders." WHEW.