How the Open Window of Vatican II Led to the Stale Air of Covenant Communities

Part Recap Essay, part Deep Dive

This week, we’re doing something a little different. Today’s essay is a deep dive into the history and theological roots of covenant communities—intentional Catholic groups that rose to prominence in the aftermath of Vatican II. Then, on Friday, we’ll bring you a personal and powerful guest essay from author Audrey Clare Farley, reflecting on her own upbringing in one such community: the Lamb of God in Baltimore, Maryland.

In Monday’s Whiplash episode, we sat down with Audrey, a writer, editor, and scholar of twentieth-century American culture. She holds a PhD in English literature from the University of Maryland, College Park, and is the author of The Unfit Heiress and Girls and Their Monsters. Her current work—an essay collection about her childhood in the Lamb of God community—offers rare insight into a uniquely insular Catholic subculture.

Content statement: Please note this piece includes discussions of abuse of power, sexual abuse and harassment, and restrictive gender roles.

In our conversation, Audrey described what it was like to grow up within a covenant community and how groups like Lamb of God reflected a broader post–Vatican II movement toward intentional and often separatist forms of Catholic living.

Covenant communities emerged in the 1970s, largely in response to the sweeping reforms of the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), commonly referred to as Vatican II. These reforms—sparked by global movements for civil rights and gender equality—modernized many aspects of Catholic worship and governance. The Novus Ordo Mass replaced the Latin rite with vernacular language, Church doctrine underwent revisions, and for the first time, the Vatican formally acknowledged the role of laypeople in shaping Catholic life.

Today’s essay explores that historical backdrop in more depth, tracing how and why covenant communities formed—and what they tell us about power, authority, and control in the modern Church.

Charismatics, Cursillos, and Covenants

In 1967, the Holy Spirit showed up at a Catholic university retreat—and never left. What started as a handful of students praying in tongues and falling to the floor sparked one of the most explosive and controversial movements in modern Catholic history: the Catholic Charismatic Renewal.

Suddenly, lay Catholics were speaking of visions, miracles, and personal encounters with Jesus in living rooms and parish halls across the world. It wasn’t a new denomination, but it felt like a different Church—one on fire. Borrowing heavily from Pentecostal and charismatic Protestantism, this movement brought intense emotional worship, healing prayer, and supernatural gifts into a tradition known more for incense and order.

At its heart was the “baptism in the Holy Spirit”—not a new sacrament, but a powerful reawakening of grace already given through Baptism and Confirmation. It promised to make the faith feel alive. But for all its energy, the Renewal raised big questions: How do you bottle spiritual fire without burning down the house? How far can Catholicism stretch without snapping? And was this a revival—or a schism?

In Apostolicam Actusotitatem (Decree on the Apostolate of the Laity), the Church reaffirmed that all people, including lay members of the Church are called to holiness. This was a large part of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal, which was a movement that emerged in the early to mid 1960s in the Midwestern United States.

One of the most influential figures within the Catholic Covenant communities–Stephen B. Clark–was himself a convert to Catholicism. Stephen B. Clark didn’t just want revival—he wanted order. As one of the architects of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal, Clark helped channel the chaos of spiritual awakening into something far more structured: covenant communities bound by rules, hierarchies, and lifelong commitments.

What began with tongues and prophecy in a cramped Ann Arbor apartment quickly evolved into a sprawling movement of tightly governed lay communities, complete with manuals, leadership structures, and vows of obedience. At the center was Clark’s vision of radical discipleship—one that demanded total commitment, communal living, and submission to authority as the price of spiritual power. The Holy Spirit might have lit the fire, but Clark built the walls around it.

While at Yale University in the late 1950s/early 1960s, he converted to the faith and was closely involved in the Thomas More House Catholic Student Ministry. Led by Fr. James T. Healey, this community would later influence his interest in creating a community that would support and practice Catholicism outside of Mass. Clark first learned about the Cursillo movement on a mission trip to Mexico.

At first glance, the Charismatic Renewal looked like the opposite of rigidity—ecstatic worship, spontaneous prayer, and emotional encounters with the divine. But underneath the singing and falling in the Spirit was a different current: one of discipline, order, and spiritual warfare. Influenced by Cursillo’s call to form “soldiers for Christ,” Clark began fusing charismatic fervor with a deeply militant vision of community life—one that emphasized obedience, hierarchy, and total commitment.

As Billy Kangas wrote, “the movement recruited men to be soldiers in a new militant approach to the Church.” Originally established in Spain between 1940 and 1949, the Cursillo movement emphasized a deeply personal relationship with God and small group fellowship. Similar to Vatican II’s emphasis on involving the laity, the Cursillo movement was originally founded out of Catholic Action and through Cursillo, or short courses of community, brought people to work, pray, and study together to become better Christians and evangelize. In 1957, the first Cursillo was held in the United States in Waco Texas, and soon spread throughout the southwest and later southern United States.

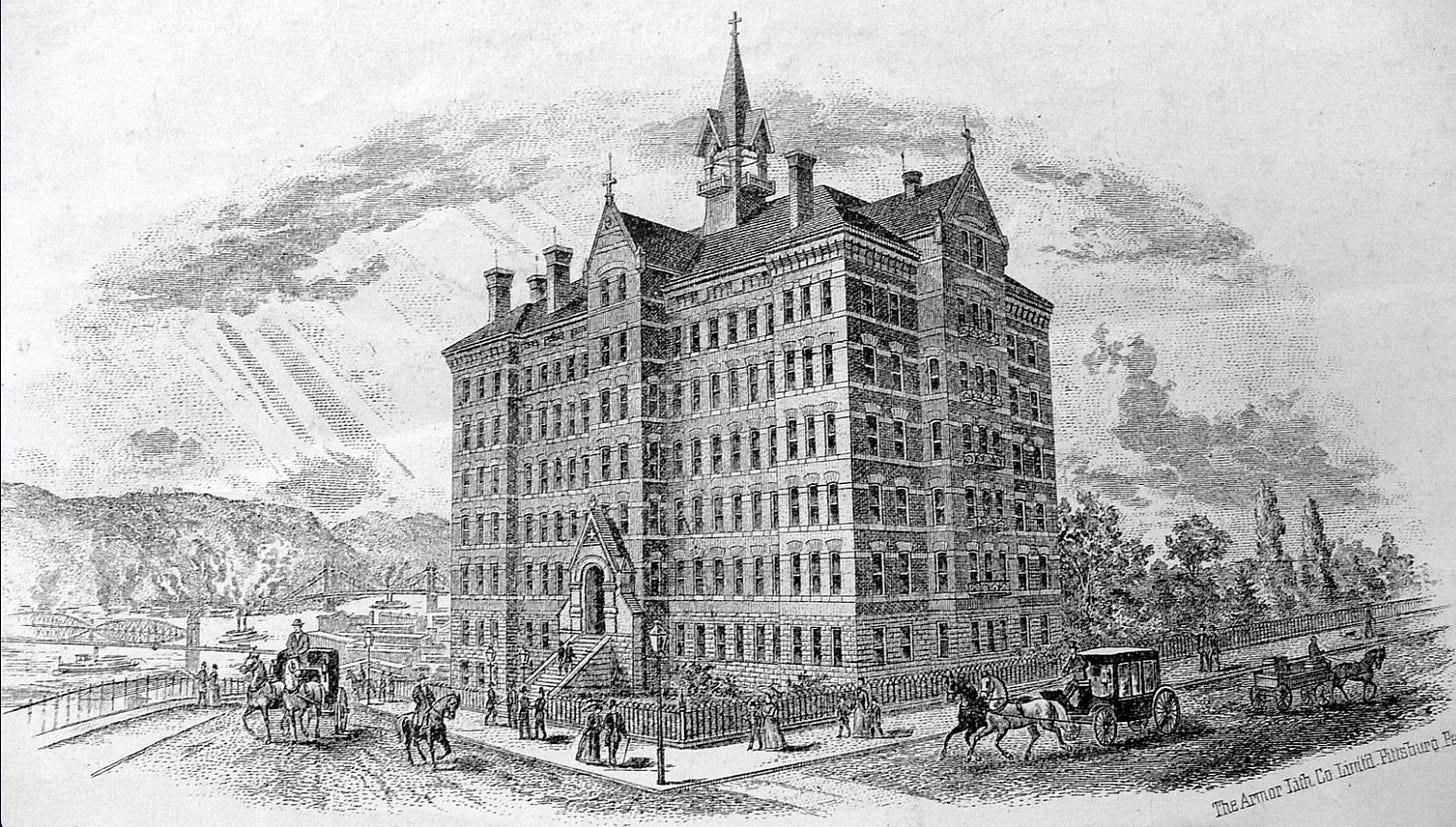

In 1963, the Archdiocesan Cursillo Center was founded in Chicago, and Clark attended a retreat there during his first semester of grad school. After his first semester, he began to organize additional Cursilo retreats which would later serve as vital leaders in the Charismatic community he hoped to found. Kangas traced the history of this movement, including Clark’s meeting in 1967 with William Storey, a history professor, and Ralph Keifer, a theologian, at Duquesne University.

Duquesne University and the Birth of a Charismatic Movement

What began as a seemingly spontaneous and deeply spiritual event at Duquesne University in 1967—the so-called “Duquesne Weekend”—is hailed by insiders as the miraculous birth of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal, a movement now boasting over 120 million adherents worldwide. Yet, behind the glowing testimonies of being “baptized in the Spirit” and falling into ecstatic states lies a story of fervent emotionalism packaged as spiritual awakening. Participants describe dramatic physical manifestations and overwhelming emotional highs, but these experiences quickly led to division and tension, with traditional groups fracturing under the pressure of this new, intense form of worship. Far from the quiet reverence many associate with Catholicism, this renewal injected a Pentecostal-style fervor that unsettled existing communities and challenged long-standing norms.

Shortly after meeting with Clark, Storey and Keifer claimed to be “baptized in the Holy Spirit.” The movement spread among Duquesne University students and professors, and later to the University of Notre Dame. Members would sometimes speak in tongues and convulse as if their bodies were inhabited by another person, similar to Pentecostal traditions. These charismatic traditions, as Audrey Farley shared with us this week on the podcast, are strikingly different from traditionalist Catholic ones where Mass and experiences of the Holy Spirit are deeply ritualized.

Rather than simply renewing traditional Catholic piety, the charismatic movement plunged believers into an intense, visceral encounter with the Holy Spirit—experiences more reminiscent of ecstatic mystics like Saint Teresa of Avila than the quiet rituals of typical parish life. Claiming that iconic figures such as St. John Vianney possessed the “gift of tongues,” proponents have boldly recast centuries-old saints as forerunners of this distinctly modern, American-born revival—a move that blurs historical lines and fuels the movement’s aura of supernatural legitimacy.

As Richard J. Bord and Joseph E. Faulkner reveal in The Catholic Charismatics, this movement was less about theological nuance and more about breaking free from the “secular environment”—a vague and often alarmist term used to describe the outside world that must be guarded against like a corrupting force. Clark, hailed as a key architect of this radical transformation, helped forge a movement that promises liberation but often demands conformity to a new, electrifying—and sometimes controlling—spiritual regime.

Much like the seismic shift brought about by the Novus Ordo Mass—with its move to vernacular language, the introduction of guitars and other contemporary instruments replacing traditional chanting, and the vivid use of felt banners as noted by Heidi Schlumpf on last week’s podcast—the Charismatic movement ignited a radical transformation in Catholic worship and community life starting in the 1970s. This movement changed how Catholics worshipped and birthed a new model of tightly knit, rule-bound communities known as covenant communities. These communities, which include influential umbrella organizations like the Sword of the Spirit and People of Praise, sought to fuse charismatic spirituality with a disciplined, mission-driven way of life.

The term “covenant communities” goes beyond mere spiritual gatherings—it refers to structured groups governed by strict sets of rules that shaped every aspect of members’ daily lives, relationships, and ministry. Two of the earliest examples, the Word of God community in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and True House and People of Praise in Ann Arbor and South Bend, Indiana, were founded in 1970 and 1971, respectively. These communities quickly multiplied, expanding their reach and influence, notably with the establishment of the Lamb of God community in Baltimore, Maryland—where writer Farley was raised.

Farley’s critical analysis in the Baltimore Sun stands as one of the first investigative pieces exposing the secretive and highly controlling nature of these covenant communities, highlighting the tensions between charismatic renewal’s promise of spiritual freedom and the reality of strict social and spiritual control behind closed doors. Understanding this historical context is crucial because it reveals how what started as a vibrant renewal movement also carried within it seeds of high-control group dynamics that still demand scrutiny today.

The Covenant Network: How Lamb of God, People of Hope, and Servants of Christ Shaped a Culture of High Control Catholicism

Building on the rise of covenant communities as disciplined, rule-driven enclaves within the Charismatic movement, some of these groups took separatism to an extreme, erecting walls not just around their faith but around every aspect of daily life. What began as a search for deeper spiritual connection quickly morphed into tightly controlled environments where obedience was demanded, personal freedoms were restricted, and leadership often blurred the line between guidance and authoritarian control. The Lamb of God community in Maryland is a stark example of this dynamic—where the promise of spiritual renewal intertwined with strict behavioral codes, rigid gender roles, and a growing isolation from the “secular” world.

As we dive deeper, the stories from Lamb of God and other similar communities reveal a pattern of secrecy, power imbalances, and troubling abuses that belie the joyful, free-spirited image many associate with charismatic Catholicism.

Founded by Maryland residents Dave and Cheryl Nodar, Father Joe O’Meara and several others, Lamb of God sought out separatism from the wider “secular” world, complete with their own covenant that restricted how people acted, dressed, and fulfilled their roles in the community. In this community, some Catholics were “baptized in the Spirit” and spoke in tongues, often the children and adults with the highest standing or key connections to power in the community.

Related: read a lived experience story from someone who lived in Lamb of God here.

Within this community, gender roles were strictly enforced by policing behavior and dress, priests and lay leaders overstepped critical boundaries, and members were encouraged to separate from the external, “secular” world similar to St. Mary, Kansas.

The community later dissolved in the mid to late 1990s following a deeper investigation into its finances and accusations, alongside other communities, of cult-like behavior. And the experiences that Farley describes resonate with those shared by Karen Ann Coburn in her podcast Shadow of Hope about the People of Hope Catholic Covenant Community in Berkeley Heights, New Jersey. The podcast offers a view into the secretive life within covenant communities and as she explains, “what price are we willing to pay to belong to something bigger than ourselves?”

Mary Pezzulo, who attended Franciscan University while pursuing her Master’s degree in philosophy and Catholic bioethics, also wrote that the People of Hope community had strikingly similar characteristics, arguably “the same cast of characters,” Pezzulo wrote as the Servants of Christ the King Intentional Community in Steubenville, Ohio. Pezzulo specifically called out Father Michael Scanlan, a well known Catholic Charismatic leader and Steubenville founder, who was accused of sexual assault and abuse by community member and students at Franciscan. He was involved in the Servants of Christ covenant community as well as Franciscan University.

Three years ago, Pezzulo called out the Servant of Christ as a key example of cult-like communities within Catholicism, sharing a copy of the policy notebook from the Sword of the Spirit association of Christian communities. These policies, written in 1989, were further used by the Servants of Christ community in Steubenville. Servants of Christ was shut down by the Church in 1991. Pezzulo describes herself as a recovering Charismatic, and writes about the legacies of sexual violence inside covenant Catholic communities.

Pazzulo, like Farley, is one of a few people who are beginning to speak publicly about their experiences within these communities, and to highlight the intense power abuses that occurred within them. Covenant communities continue to exist, including the Sword of the Spirit whose policy notebook from 1989 is linked above. And covenant communities are coming up more and more in the news, despite little research into their beginnings and long-term impact. For example, Amy Coney Barrett, appointed to the Supreme Court by President Trump in 2020, was raised in and is a member of People of Praise.

Note: It’s important to recognize that covenant communities are part of a wider tradition of intentional Catholic communities that predate the 1970s, including those created by members of the Catholic Workers Movement. As religious studies scholars Lisa Oakley and Kathryn Kinmond explain, it’s largely when religious communities cultivate a culture of shame, prohibit or discourage questioning, and use scripture to control group dynamics that groups can become harmful. Accountability is a key part of the puzzle, especially from outsiders.

Conclusion

The story of covenant communities reveals how longstanding impulses toward high control and authoritarianism within Catholicism found new expression in the post–Vatican II era. The reforms of Vatican II opened doors for renewal, participation, and spiritual vitality, but they also provided fresh language and frameworks that some groups used to justify tightly governed, insular communities. What began as an invitation to deeper freedom and engagement was too often co-opted by movements that masked rigid obedience, separation, and control behind the rhetoric of charismatic renewal and covenant commitment.

Audrey Clare Farley’s personal reflections, alongside critical voices like Mary Pezzulo and Karen Ann Coburn’s podcast Shadow of Hope, reveal the lived realities behind these tightly governed groups: the policing of gender roles, the silencing of questions, and in some cases, abuses of power that went unchecked for decades. Their courage in speaking out shines a light on what has often been hidden or dismissed as isolated incidents, showing instead a pattern replicated across communities such as Lamb of God, People of Hope, and Servants of Christ. This history complicates the narrative of charismatic renewal, reminding us that spiritual movements, even those born from profound encounters with God, are vulnerable to human flaws and institutional failures.

As covenant communities continue to exist and evolve, their legacy demands careful scrutiny—not only from within the Church but also by scholars, survivors, and the wider public. The example of Amy Coney Barrett’s membership in People of Praise highlights how these groups intersect with broader cultural and political spheres, underscoring their ongoing relevance. At the same time, the insights of religious studies scholars like Lisa Oakley and Kathryn Kinmond emphasize the vital importance of accountability, transparency, and the freedom to question in safeguarding religious communities from harm.

Ultimately, the history of covenant communities challenges Catholics—and all faith communities—to wrestle honestly with the tension between spiritual renewal and institutional control. It calls for a renewed commitment to building communities that foster belonging without coercion, faith without fear, and leadership without abuse. Only through this reckoning can the fresh winds of Vatican II truly breathe new life into the Church without allowing the stale air of high-control environments to settle once more.

In the end, it is not any one theology, reform, or spiritual movement that leads communities to stray into High Control methods—but rather, problems arise from the failure to center healthy boundaries, welcome open dialogue, and include the full participation of all people, especially those on the margins. Without these, even the most well-intentioned groups risk becoming rigid, insular, and harmful, no matter how noble their beginnings.